Diphtheria

Key facts

-

Diphtheria is a very serious disease that causes breathing difficulties, heart failure and in some cases, death.

-

In Australia, diphtheria is now rare. Vaccination is recommended so that babies and children can’t catch diphtheria from people around them who have travelled to countries where the disease is still common.

-

Vaccines are the best way to protect your child from diphtheria.

On this page

- What is diphtheria?

- What will happen to my child if they catch diphtheria?

- What vaccine will protect my child against diphtheria?

- When should my child be vaccinated?

- How does the diphtheria vaccine work?

- How effective is the vaccine?

- Will my child catch diphtheria from the vaccine?

- What are the common reactions to the vaccine?

- Are there any rare and/or serious effects to the vaccine?

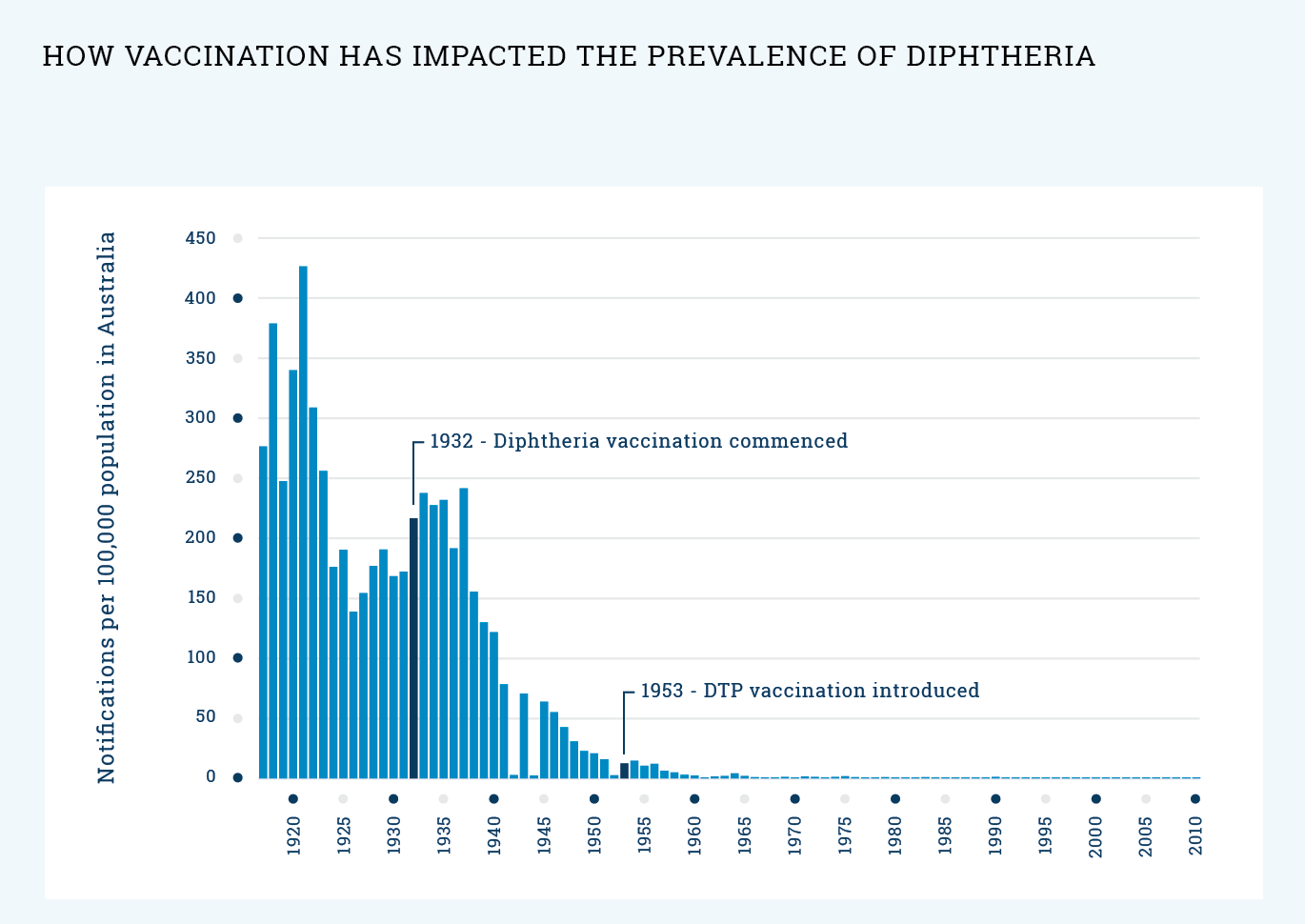

- What impact has vaccination had on the prevalence of diphtheria?