Diphtheria

Key facts

-

Diphtheria is a serious disease that can cause breathing difficulties; heart, brain and nerve damage; and, in some cases, death.

-

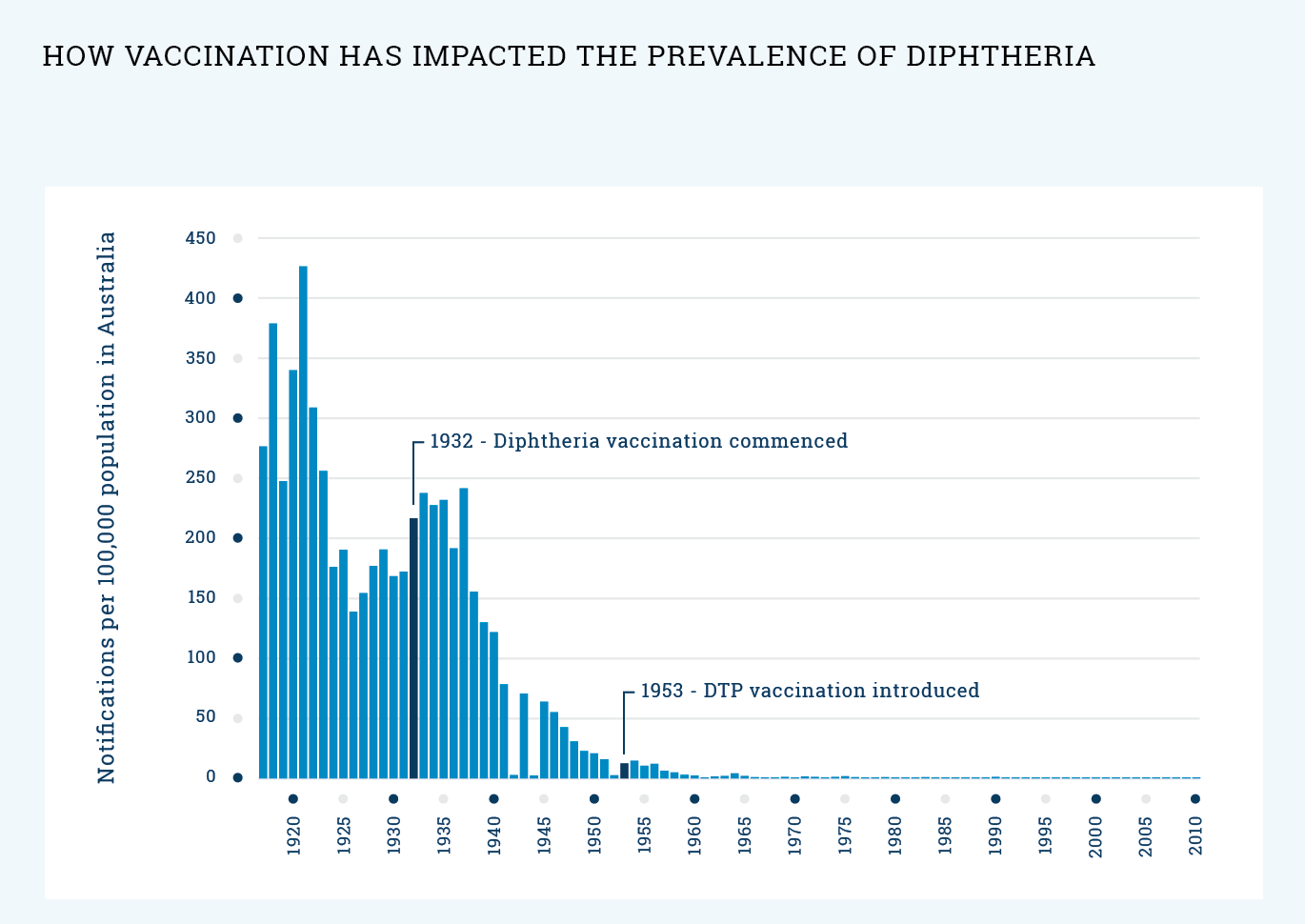

Due to the vaccination program, diphtheria has been rare in Australia for a long time, but recently a small number of cases have been reported again.

-

In Australia, all infants and young children are recommended to be vaccinated against diphtheria. To keep this level of protection in adolescence, a booster dose is recommended for all 12- and 13-year-olds.

On this page

- What is diphtheria?

- What will happen to my adolescent if they catch diphtheria?

- What vaccine will protect my adolescent against diphtheria?

- When should my adolescent be vaccinated?

- How does the diphtheria vaccine work?

- How effective is the diphtheria vaccine?

- Will my adolescent catch diphtheria from the vaccine?

- What are the common reactions to the vaccine?

- Are there any rare and/or serious side effects to the vaccine?

- What impact has vaccination had on the spread of diphtheria?

- What if I still have questions?