Hib

Key facts

-

Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b) causes a variety of serious illnesses, including swelling around the brain (meningitis), blood poisoning (septicaemia), swelling in the throat and lung infections (pneumonia).

-

Children who get Hib infections before two years old do not usually develop natural immunity.

-

Hib-containing vaccines are the best way to protect your child from Hib.

On this page

- What is Hib?

- What will happen to my child if they catch Hib?

- What vaccine will protect my child against Hib?

- When should my child be vaccinated?

- How does the Hib vaccine work?

- How effective is the vaccine?

- Will my child catch Hib from the vaccine?

- What are the common reactions to the vaccine?

- Are there any rare and/or serious side effects to the vaccine?

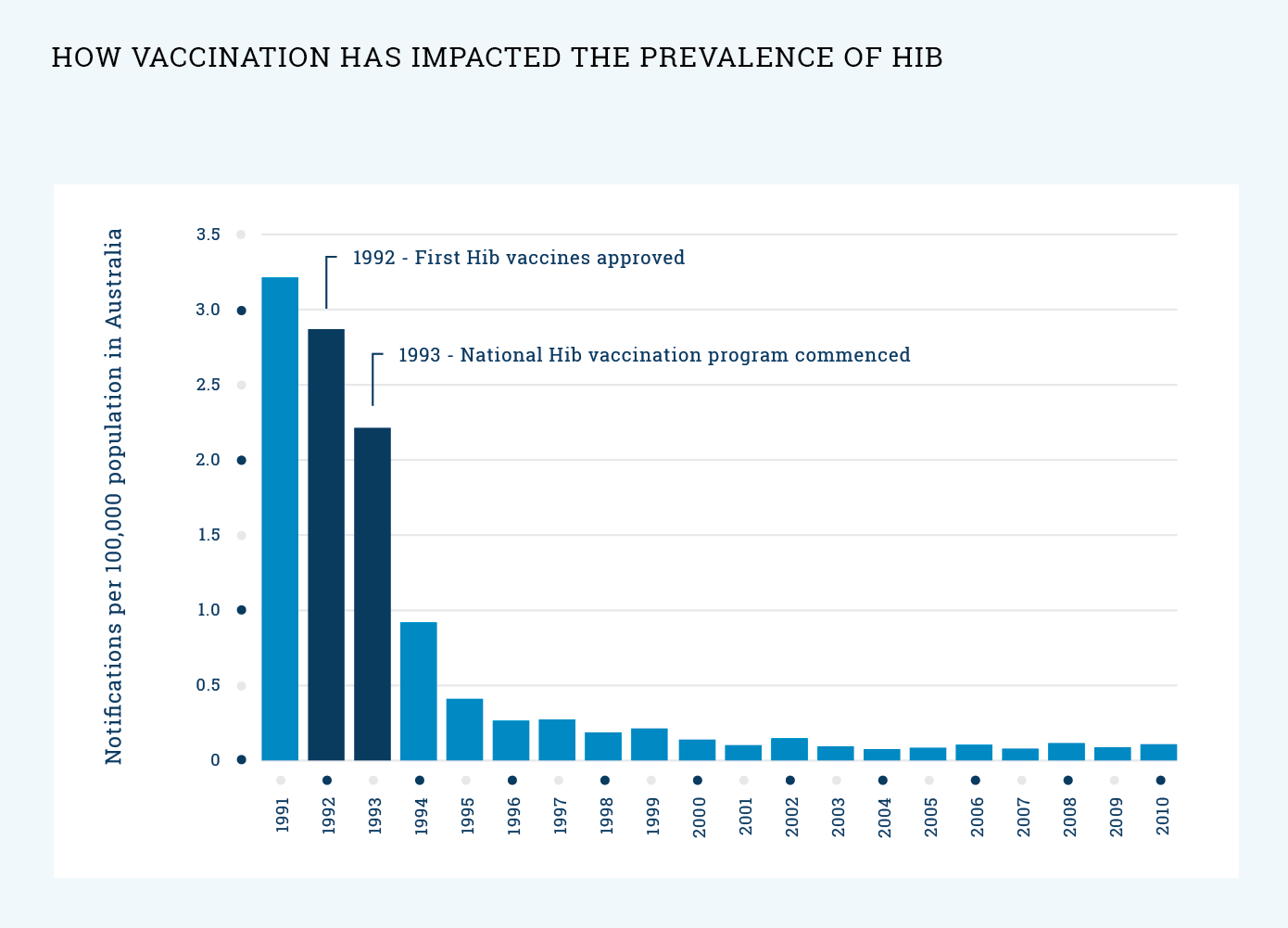

- What impact has vaccination had on the prevalence of Hib?